The modern postcard was born in 1869, the widely acknowledged offspring of Austrian economist Dr Emanuel Herrmann (1839–1902), who prompted the Austrian government to issue the first official “correspondence cards” in October of that year. Although Heinrich von Stephan (1831–1897), the Prussian (later Imperial German) Minister of Posts, had proposed something similar in 1865, his idea was stillborn, and in 1870 both the North German Federation and Great Britain issued official, reduced-rate cards on the Austrian model. In 1871, Canada and six European countries issued their first official cards, and by 1874 many other countries, including the United States, had followed suit. In the U.S., use of the word “Postal” denoted government issue cards, and “Post” the privately issued ones, a distinction that was soon widely ignored.

In the era before widespread adoption of the telephone, the new postal cards facilitated communication through the quick, efficient, and low-cost exchange of brief messages, without the need of formal stationery, envelopes, and postage stamps. Unlike formal, written letters, postcards demanded only minimal levels of literacy, and their introduction helped democratize the act of correspondence by bringing it within reach of all but the very poorest. In large cities with multiple daily postal deliveries, a card might be received and replied to on the very day of its dispatch. For several decades these cards were the most popular and efficient form of communication by which people could arrange meetings and dates, advertise products and services, place orders with merchants, and keep in touch with family and friends, often over great distances. Until 1886, however, they were generally only valid for use within the country of issue. Canada included Newfoundland within its domestic rates in November 1872, but cards sent to the U.S. and Britain still required an additional one-cent stamp. As of January 1875, however, Canada and the U.S. had agreed to accept each other’s letters and cards at the same domestic rate. In July 1878, Canada joined the General (later Universal) Postal Union, which required member nations to accept each other’s cards at one-half the letter rate.

Pre-paid, government issue postal cards were printed on plain card stock, their backs exclusively reserved for addresses, and the other side for messages. By the 1880s, however, proprietary cards were being produced in France and Germany with illustrations small enough to leave space for written messages to be added. Official postal cards with illustrations, distributed in conjunction with fairs and exhibitions held in Paris in 1882, London in 1891, and the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1892–93 (where they were sold from 5-cent vending machines), did much to popularize picture postcards. Cards, explicitly labelled “Private,” were accepted at the reduced, one-penny rate in Canada from January 1895, and in the U.S. from May 1898.

As official acceptance of private cards became widespread, a major publishing industry grew up to supply an eager public with a profusion of printed cards that featured either original artwork or photographic images reproduced by photogravure or by colour lithography. German printers in particular were noted for their high quality product, and came to dominate the market for handsomely produced picture postcards, sometimes featuring embossing and other embellishments, that were commissioned by American, British, and other foreign publishers. This export trade was only curtailed by the outbreak of war in 1914. Major publishers of picture postcards included the London firm of Raphael Tuck & Sons, which began issuing numbered sets of view postcards in 1898 and opened a New York office in 1900, and James Valentine & Sons of Dundee, who also began publishing postcards in 1898, and later opened offices in Montreal and Toronto, where they published a total of 20,000 different Canadian scenic postcards. Moreover, Canada did not lack a domestic postcard industry, which was represented by firms such as Warwick Brothers & Rutter, W.G. MacFarlane of Toronto, and Cloke & Son of Hamilton.

“Divided-back” picture postcards, which permitted both message and address to share the same side of the card, leaving the other side entirely free for the picture, were officially authorized in Britain in 1902, in France in 1903, and in Canada the following year. The Universal Postal Union’s Sixth Congress, meeting in Rome in June 1906, endorsed the acceptance of divided-back cards by all member nations, thus giving the graphic designers a wider palette for their creative efforts.

The official acceptance of privately-produced, picture postcards transformed a simple and cheap means of conveying brief personal and commercial messages into a colourful and artistic medium to commemorate public holidays, celebrate personal milestones, or document one’s travel and tourism. By the early years of the 20th century, an ever-increasing number of cards — amounting to several billion — were posted annually. The proliferation of picture postcards, dismissed as a “craze” by many observers, received further impetus with the appearance of the real photo postcard.

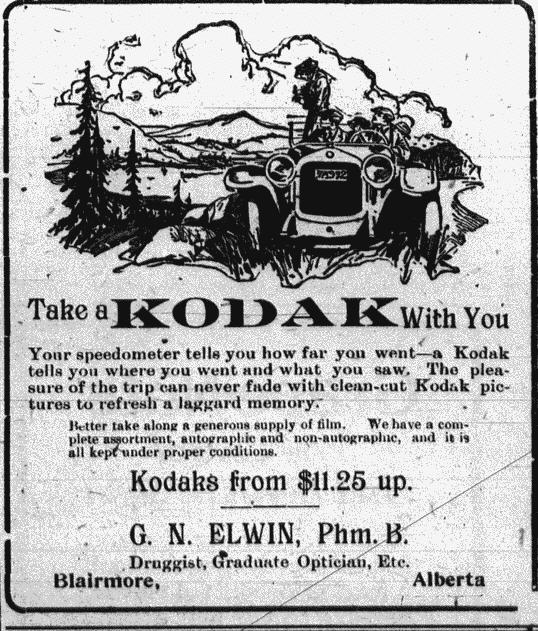

In 1888 George Eastman, inventor of roll film, marketed his first “Kodak” camera, loaded with film for 100 exposures, and designed for the amateur photographer. In 1900 the Eastman Kodak Company introduced the first Kodak “Brownie,” a simple box camera priced at $1, which really launched the hobby of amateur photography, for the owner could now load and unload the rolls of film for developing and processing, without sending the entire camera back to the factory. But Kodak’s greatest boost to the postcard craze really began in 1903 with the introduction of the Kodak Folding Pocket Model 3A camera. Produced until 1941, it was a small, folding bellows camera, priced from as low as $12, that yielded postcard-size negatives (3.25 x 5.5 inches / 83 x 139 mm). Kodak distributed its photo print papers, both the “Velox” and (after 1904) the cheaper “Aso” brand, precut to the same size, with the standard postcard grid format printed on the backs. Despite competition from other companies’ photo papers in postcard format, such as Ansco’s “Cyko,” Artura’s “Artura,” Burke & James’ “Rexo,” Defender’s “Argo,” and Kilburn’s “Kruxo,” Kodak papers accounted for 70 percent of such sales prior to 1914, while it sold an annual average of 45,000 Model 3A cameras during the same period.

In 1914 Kodak introduced the Model 3A “Autographic” version, which allowed the photographer to open a narrow gate at the back of the camera, and inscribe captions directly on negatives, that would be reproduced, with the image, on the final prints. This made later identification easy, but the need to write backwards explains the often mediocre to generally poor quality penmanship displayed by these captions. In 1907 Kodak introduced the Model 3A Graflex, originally developed by the Folmer & Schwing Company, a professional-grade camera that could be adapted with a special attachment to take panoramic photographs. Panoramic photo postcards, usually of large groups such as graduating classes or military formations, or townscapes such as the one of Regina in this exhibit, are relatively rare, perhaps because their awkward format makes them harder for collectors to store and preserve. Although Eastman Kodak dominated the North American photographic market, in part by buying out its competitors, the Mandel Post Card Machine, produced by the Chicago Ferrotype Company, was popular with street and carnival photographers because it produced positive prints directly on photo postcard paper, without negatives. Mandel cards are otherwise largely distinguished by the poor quality of their images. Picture postcards printed lithographically could be multi-coloured, often quite gaudily so. Although most true photo postcards were black and white prior to the introduction of colour film in the 1930s, colour could be added from a limited palette by toning the photographic image, or by tinting the binder and emulsion base on the paper, or a combination of both.

Picture postcards appeared in such profusion during the “Golden Age” of the postcard, or roughly from 1900 to 1920, and bear such a variety of images, that they almost defy classification by subject. The broadest general categories are “view” cards and “topical” cards. The former were produced largely as tourists’ souvenirs, and depict major cities, especially their public buildings, monuments, and artworks, or scenery and landscapes. The topical run the gamut from cards advertising goods and services, promoting civic pride and patriotism, chronicling local achievements, events, and disasters, celebrating holidays and other special occasions, and, at a more intimate level, recording people’s daily life, work, and surrounding environment. The massive immigration and internal migration to the Prairies, as well as expanding tourism during this “Golden Age” era, account for the proliferation of view cards and topical cards depicting the region. With the appearance of the earliest specialty cards, hobbyists began to collect them and keep them in albums, a pastime dubbed “Deltiology” by American collector Randall Rhodes in the 1930s. True, or “real” photo postcards offer an astonishing level of detail, which, because they are real photographs, are easily scaleable, that is, capable of considerable enlargement without loss of density or clarity. Picture postcards represent a rich and still largely untapped resource for historians, genealogists, and other researchers.

Thanks largely to the tourism aggressively promoted by the Canadian Pacific and Canadian National Railways, spas and resorts such as Banff and Jasper in the Rockies could support professional photographer Byron Harmon (1876–1942), who produced many photo postcards, and whose work is highly prized today by collectors. However, with the exception of the national parks, resorts, and the City of Winnipeg, the local markets for souvenir view cards of prairie subjects was too small through most of this period to attract or support large-scale production and sales by the large printing and publishing firms. Still smaller was the demand for those very personal cards produced to keep in touch with distant family and friends, to reassure them about one’s progress and success in carving out a new life on the prairie frontier. Many such topical cards of local interest must have been produced in quantities of no more than 50, and often fewer still, which explains their relative scarcity. While Eastman Kodak offered a photo postcard processing and printing service by mail, the majority of local interest, topical photo postcards were produced locally by part-time professional, itinerant, or amateur photographers. Few of the sparsely populated towns of the Prairie Provinces, so richly represented in our postcard gallery collection, were large enough to support a full-time photographer, so card production and sales were often undertaken by local merchants working in their dry goods stores and pharmacies, and by itinerants who travelled the back roads from farm gate to village festival to town during the summer months, often as a second, seasonal occupation. Their collective labours have left us with a rich photographic legacy documenting one of the most dynamic and formative eras in our history, as we hope The Last Best West: Glimpses of the Prairie Provinces from the Golden Age of Postcards exhibit bears witness.

Merrill Distad

Associate University Librarian

(Research & Special Collections Services)

Alberta Digital Royal

Commissions

Alberta Digital Royal

Commissions Alberta

Folklore and Local History

Alberta

Folklore and Local History Alberta

Folklore and Local History Photographs

Alberta

Folklore and Local History Photographs Atlas

of Alberta Railways

Atlas

of Alberta Railways Educational Resources

Educational Resources Copyright

and Usage

Copyright

and Usage Spot an

error?

Spot an

error? Peel's Roadmap

Peel's Roadmap Questions and Answers

Questions and Answers Related

Websites

Related

Websites